When you go to the grocery store to pick up fresh fruit and vegetables you may take for granted that the produce you need will be there. But it’s not as though there’s a farm behind the store. It’s the interconnected supply chain that links growers, drivers and retailers that ensures store shelves are well stocked.

Similarly, before natural gas ever reaches your home it flows through a well-developed supply chain linking producers in BC and Alberta to customers all over the Pacific Northwest. In fact, the gas we use can travel more than a thousand kilometres on its journey to BC furnaces and fireplaces.

A brief history of B.C. natural gas

To understand how the gas system works today, it helps to know a little about the story of natural gas in BC. Although gas reserves were discovered all over the province starting in the late 1800s it wasn’t until 1947 with the opening of the province’s first successful gas well, Peace River No. 1, that the story gains momentum. From this first well came a wave of oil and gas development that forever changed northeast BC into a world-renowned energy producing region.

By the 1950s, pipelines began to branch out from the energy-rich north, to the energy-hungry cities to the south. Among them was a natural gas pipeline completed in 1957 by Westcoast Transmission Co. that stretched from the town of Taylor to a pipeline in Washington state more than 1,000km away. This link became the backbone of the natural gas system in the Pacific Northwest on both sides of the border.

In the decades since then, the gas market has continued to develop with new links and new companies adding to and shifting the supply chain.

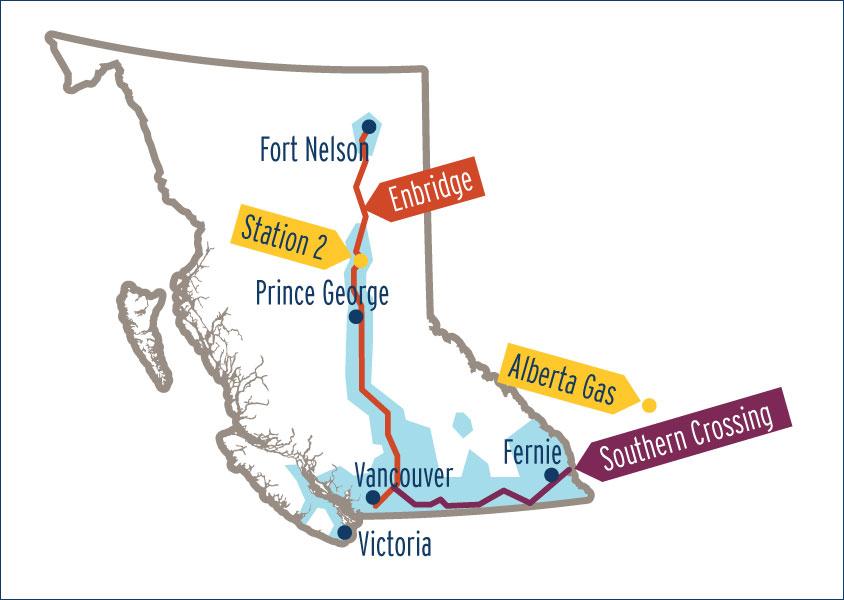

Now, much of the output from the wells and processing plants in northeastern BC flows to a market hub called Station 2 located near Chetwynd, where gas is bought and sold. From there gas can flow along the Westcoast pipeline (now owned by Enbridge and known as BC Pipeline T-South) to the U.S. border, east along TransCanada’s NGTL pipeline to Alberta and beyond, or north along Enbridge’s T-North pipeline.

Where FortisBC fits in

FortisBC is the leading energy provider in BC, supplying natural gas to more than one million customers. About three-quarters of the gas FortisBC supplies to its customers comes from Station 2. Most of the rest comes from a market hub in southern Alberta.

While FortisBC owns a large system of gas lines, it relies on the Enbridge-owned T-South pipeline to move gas it buys from Station 2 to its Interior, Lower Mainland and Vancouver Island systems. You can think of it like a road network with Enbridge’s pipeline acting as an interprovincial highway with off-ramps into FortisBC’s system at Savona west of Kamloops, Kingsvale and at Huntingdon in Abbotsford. But it’s not the only route. In 2000, FortisBC completed the Southern Crossing pipeline, which connects its system to a market hub in Alberta increasing access to natural gas and improving the security and reliability of natural gas supply in the province.

FortisBC is T-South’s largest customer, purchasing roughly one-third of the gas sold on the pipeline, but it’s far from the only customer. Another large customer is Puget Sound Energy, which serves about 750,000 gas customers in Washington. Other customers range from industrial companies to utilities.

In the event of cold weather or an emergency, the Pacific Northwest’s interconnected system allows FortisBC and other utilities to have more flexibility to keep gas flowing. FortisBC can store gas at underground facilities in Washington and Oregon and bring gas back when needed during the winter.

FortisBC can also store gas at its two liquefied natural gas facilities at Mt. Hayes on Vancouver Island and Tilbury Island in Delta, which can provide several days of gas supply in the winter.

Future of BC’s gas system

In the 70 years since the first successful well was drilled in BC, the province’s natural gas network has seen major changes. But some of the biggest changes may be still to come.

The demand for natural gas continues to grow with the prospect of liquefied natural gas export projects, as more homes are built with gas appliances and as more vehicles run on natural gas. The gas system is adapting to these changes with both TransCanada and Enbridge proposing upgrades and expansions to the pipelines that feed into the FortisBC system.

FortisBC is already hard at work enhancing its system including in the Lower Mainland where an 11-kilometre gas line upgrade was built in 2017 and a 20-kilometre gas line is being upgraded through this year. It’s also planning a series of system upgrades throughout the BC Interior to enhance the integrity of the gas line system. The company is also aiming to diversify its gas supply and is in the early stages of planning a 161-km extension of its Southern Crossing pipeline to bring more gas to the Lower Mainland.

These upgrades are important as the gas system becomes the backbone of a future low-carbon energy system and a key part of the provincial government’s CleanBC strategy. FortisBC is already flowing low-carbon1 Renewable Natural Gas2 captured from landfills and agricultural waste into its system. Next FortisBC is looking to increase supply and set its sights on the government’s target of 15 per cent of natural gas use to be renewable by 2030. The emissions reduction from increasing RNG supply would be enough to cover three quarters of CleanBC’s emission reductions target for buildings and homes. RNG can also reduce emissions as a low-carbon transportation fuel3 for heavy-duty vehicles like trucks and ships.

FortisBC is also exploring ways to convert surplus renewable electricity into hydrogen gas for injection into the natural gas system. Adding hydrogen could make the gas system more efficient and further reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The Pacific Northwest’s system of natural gas pipelines and storage facilities has reliably served the needs of homes businesses in the region for decades. Here in BC, FortisBC is investing in that system so that it can continue to meet today’s needs, as well as the needs of customers in the future. But as one link in the chain it will require a team effort. It will take producers, partner utilities and government working together to add resiliency to the system so that the Pacific Northwest can continue to rely on the comfort and convenience of natural gas, even on the coldest days of the year.

1 When compared to the lifecycle carbon intensity of conventional natural gas. The burner tip emission factor of FortisBC’s current Renewable Natural Gas (also called RNG or biomethane) portfolio is 0.29 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per megajoule of energy (gCO2e/MJ). FortisBC’s current RNG portfolio lifecycle emissions are -22 gCO2e/MJ. This is below B.C.’s low carbon threshold for lifecycle carbon intensity of 36.4 gCO2e/MJ as set out in the 2021 B.C. Hydrogen Strategy.

2 Renewable Natural Gas (also called RNG or biomethane) is produced in a different manner than conventional natural gas. It is derived from biogas, which is produced from decomposing organic waste from landfills, agricultural waste and wastewater from treatment facilities. The biogas is captured and cleaned to create Renewable Natural Gas.

3 The Renewable and Low Carbon Fuel Requirements Regulation has a carbon intensity for electric vehicles of 19.73 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per megajoule of energy (gCO2e/MJ) compared to Renewable Natural Gas (also called RNG or biomethane) at 10 gCO2e/MJ (weighted average). The default carbon intensity for battery electric vehicles electricity in British Columbia is 19.73 gCO2e/MJ on a well-to-wheel basis according to the Renewable and Low Carbon Fuel Requirements Regulation. The approved carbon intensities for RNG used for transportation in British Columbia are negative -86.47 to 10.5 gCO2e/MJ on a well-to-wheel basis according to the Renewable and Low Carbon Fuel Requirements Regulation. This is from the list of approved carbon intensities.